By Hon. Kent Cattani

and Hon. Paul J. McMurdie

Recently, Arizona was in the national spotlight for the sensational trial of Jodi Arias, who killed her former boyfriend. She was headline news locally, and the topic of national debate for Nancy Grace and other court watchers.

Arias’ guilt was never in doubt. The only question in the case was whether she should spend the rest of her life in prison or be executed for her horrific crime. Two juries could not resolve the issue, and she was ultimately sentenced to life without the possibility of release.

And the cost for Arizona taxpayers? The Maricopa County Legal Defender has reported expenditures exceeding $3 million to retain counsel on Arias’ behalf for the first trial alone. The overall cost of prosecuting and defending this case will obviously far exceed that amount.

Had Arias received the death penalty, the costs would have continued to mount. The death penalty process in Arizona includes state post-conviction and federal habeas proceedings that generally span a period of more than 20 years, and such proceedings would have added hundreds of thousands of dollars in costs for the prosecution and defense, not to mention judicial costs.

Death penalty proponents understandably chafe at arguments raised by defense attorneys and death penalty opponents urging the cost of the death penalty as a reason for doing away with capital punishment. The increasing cost of the death penalty arguably reflects added protections and efforts to increase the fairness of the process, and the cost thus does not add any moral dimension to an argument against the death penalty. Nevertheless, the cost of the death penalty should not be ignored.

The old adage that the death penalty is cheaper than housing murderers in the department of corrections is simply wrong. The Arizona Department of Corrections reports that the cost of housing a prison inmate is around $24,000 per year. If Arias lives to the age of 70 it will cost the State of Arizona $840,000. The first trial alone cost considerably more than that.

National Judicial College.

In Arizona, as in most jurisdictions, the decision to seek the death penalty is made by a local prosecutor — the elected County Attorney. And the primary cost for the trial is borne by the County. But once a death sentence is imposed, the case shifts to the state Attorney General’s Office, and most of the costs associated with the approximately 20-year appeals process are borne by the State.

The process for determining what type of punishment to seek in a criminal case was put in place when Arizona became a state in 1912 — at a time when the cost of pursuing a death sentence was relatively insignificant and the appeals process lasted for months, rather than years. Given the dramatic increase in the cost of seeking the death penalty, and given the extraordinary changes to the death-penalty appeals process that have transpired since statehood, thought should be given to whether the process should be changed, including whether the State should have input into the charging decision and a concomitant responsibility to pay for the entire process.

Public support for the death penalty in Arizona and in other parts of the United States will likely continue for the foreseeable future, primarily because there are cases, such as terrorist bombings carried out by people like Osama Bin Laden and Timothy McVeigh, for which a life sentence is viewed to be an inadequate punishment. But such support does not necessarily extend to unbridled discretion to seek the death penalty in other types of cases, particularly where the costs of that decision will be borne by taxpayers to whom the decision maker does not directly answer. At a minimum, the decision whether to seek the death penalty in any given case should be made by someone or by a group of people accountable to those who pay for the process.

Several years ago, Robert Blecker, a criminal justice professor at New York Law School who supports the use of capital punishment (albeit to a lesser degree than it is currently being pursued in the United States), explained his views as follows: “I always knew Hitler deserved the death penalty. The question for me was, ‘Who else deserves it?’” That question remains pertinent today — perhaps even more so in light of constitutional arguments that the current death penalty process does not adequately narrow the class of individuals subject to the penalty. As to Jody Arias, there are some who believe that her crime evidenced a degree of brutality that warranted the death penalty. Others believe that Arias is not the type of person who posed a threat to anyone other than her victim, and that resources would have been better spent on other, more dangerous criminals. Certainly debates regarding what types of murders and murderers warrant the death penalty, and whether resources are better spent elsewhere, are discussions worth having.

Also relevant is the likelihood that a death sentence will be carried out. A recent study from researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill reports that the most likely outcome for a capital case once a death sentence has been imposed is that the defendant’s conviction or sentence will be reversed on appeal. Execution is only the third most likely outcome. Of the 8,466 people sentenced to death from 1976 to 2013, 38% (3,194) had their sentence or conviction overturned. 35% (2,979) remained on death row at the time of the study. Fewer than 1 in 6 defendants — 16% (1,359) — were executed. The rest died on death row of suicide or natural causes, had their sentence commuted, or were removed from death row for various reasons.

Given the current cost of pursuing the death penalty and given the current rate at which the punishment is actually carried out, maintaining the status quo makes little sense. The time has come to rethink the process by which the decision to seek the death penalty is made, including the determination as to how often and in what cases capital punishment should be sought.

Editor’s Note: Since this article was submitted, Nebraska lawmakers voted in May to abolish the death penalty, and the Connecticut Supreme Court ruled the death penalty violated its state constitution’s cruel-and-unusual-punishment provision, making them the 19th and 20th states to ban capital punishment. Oklahomans will vote in this fall’s general election on whether the death penalty should be enshrined in that state’s constitution. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in June that the use of midazolam for lethal injections does not violate the U.S. Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

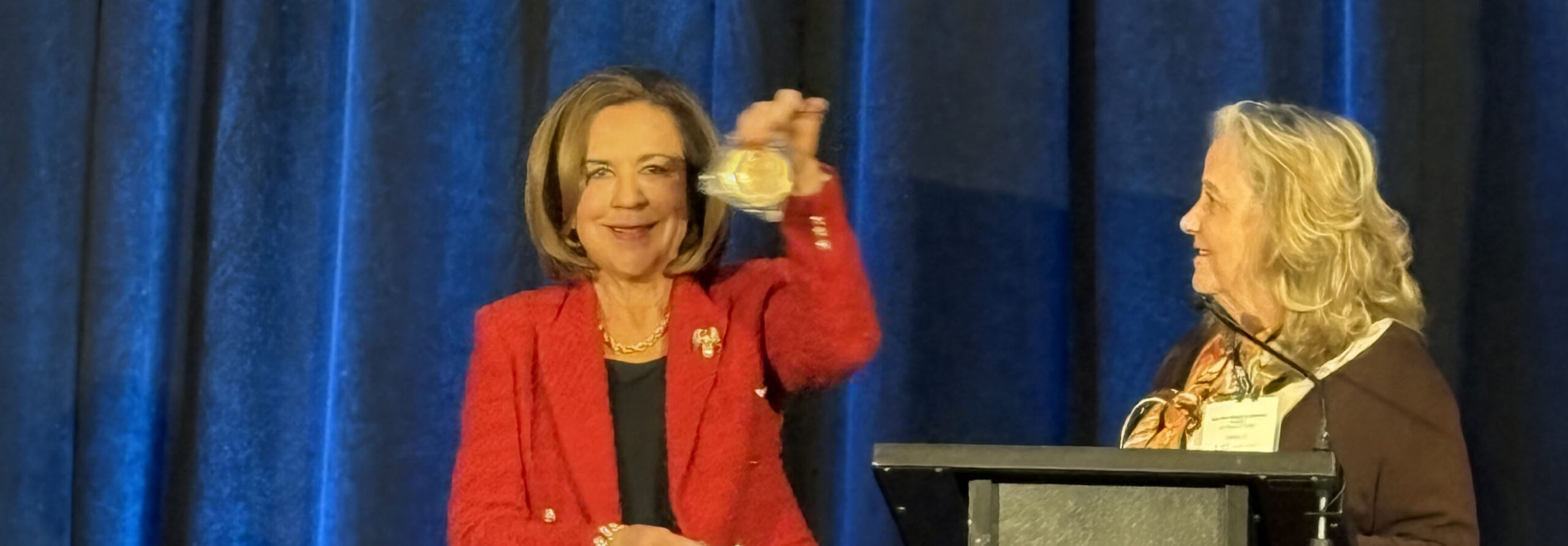

The National Judicial College has awarded Missouri Supreme Court Judge Mary Russell with the Sandra Day O�...

Emeritus Trustee Bill Neukom (left) with former Board of Trustee Chair Edward Blumberg (right) at the NJC 60...

The National Judicial College, the nation’s premier institution for judicial education, announced today t...

The National Judicial College (NJC) is mourning the loss of one of its most prestigious alumni, retired Uni...

As threats to judicial independence intensify across the country, the National Judicial College (NJC) today...