Jeanne M. Hill

“Recent inventions and business methods call attention to the next step which must be taken for the protection of the person, and for securing to the individual… the right to be let alone.”

That sentiment, which resonates strongly in today’s hyper-interactive America, was actually written in 1890 by Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis in a Harvard Law Review article entitled The Right to Privacy. The authors sounded the alarm about the use of law enforcement surveillance of the data transmitted through the telegraph and telephone.

Fast forward to the 21st century and it’s not hard to conclude what Warren, a prominent Boston attorney of his day, and Brandeis, a future U.S. Supreme Court Justice, would think about the use of drones buzzing overhead equipped with technology to record and monitor your every move. They could be justified in believing that drone technology had essentially eviscerated the privacy rights guaranteed in the Fourth Amendment.

Accurate? Depends upon who you ask.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, “drones deployed without proper regulation, drones equipped with facial recognition software, infrared technology, and speakers capable of monitoring personal conversations would cause unprecedented invasions of our privacy rights. Interconnected drones could enable mass tracking of vehicles and people in wide areas. Tiny drones could go completely unnoticed while peering into the window of a home or place of worship.”

In February 2015, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) which previously passed a law to regulate drones as unmanned aircraft in 2012, reported that it had granted 1,428 drone licenses to entities in the United States. Of all the licenses approved, the majority have been granted to local and state law enforcement.

As of this writing the US Congress has not passed any legislation to address privacy concerns surrounding drone use by law enforcement.

In 2013, Congressman Ted Poe of Texas attempted to get H.R. 637: Preserving American Privacy Act passed which would require the attorney general to publish a list of all entities, public and private, that operate drones. The bill died in Congress.

Across the United States, many states and municipalities are not waiting for federal legislation and are drafting laws to balance personal privacy rights against the need for the public’s security. According to the National Council of State Legislatures, Arkansas, Michigan, Mississippi, North Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia and West Virginia have passed legislation. Alaska, Georgia and New Mexico have adopted resolutions related to Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) drones.

- Arkansas HB 1349 prohibits the use of UAS to commit voyeurism. HB 1770 prohibits the use of UAS to collect information about or photographically or electronically record information about critical infrastructure without consent.

- Michigan SB 54 prohibits using UAS to interfere with or harass an individual who is hunting. SB 55 prohibits using UAS to take game.

- Mississippi SB 2022 specifies that using a drone to commit “peeping tom” activities is a felony.

- North Dakota HB 1328 provides limitations for the use of UAS for surveillance.

- Tennessee HB 153 prohibits using a drone to capture an image over certain open-air events and fireworks displays. It also prohibits the use of UAS over the grounds of a correctional facility.

- Utah HB 296 allows a law enforcement agency to use an unmanned aircraft system to collect data at a testing site and to locate a lost or missing person in an area in which a person has no reasonable expectation of privacy. It also institutes testing requirements for a law enforcement agency’s use of an unmanned aircraft system.

- Virginia HB 2125 and SB 1301 require that a law enforcement agency obtain a warrant before using a drone for any purpose, except in limited circumstances.

- West Virginia HB 2515 prohibits hunting with UAS.

If history repeats, don’t expect protections against invasive technologies like drones to become available through the courts in the short term.

First the case must go to trial, instead of ending with a plea bargain. If the defendant is convicted and chooses to appeal on the grounds that the new technology constituted an illegal search, then the case works its way through the appeals circuits, and given the outcomes along the way, can end up in the Supreme Court.

Many previous cases dealing with new technologies that resulted in decisions upholding an individual’s right to privacy were settled in the Supreme Court, thereby paving the way for Fourth Amendment protection in lower courts as well. But the lag time between the initial incident and a court resolution was substantial.

- Kyllo v. United States, 533 U.S. 27 (2001), held that the use of a thermal imaging, or FLIR, device from a public vantage point to monitor the radiation of heat from his home in 1992 was a “search” within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment, and thus required a warrant.

- Riley v. California, 573 U.S. ____ (2014), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case in which the Court unanimously held that the warrantless search and seizure of digital contents of a cell phone during an arrest in 2009 was unconstitutional.

- United States v. Jones, 132 S. Ct. 945, 565 U.S. ____ (2012), was a United States Supreme Court case which held that installing a Global Positioning System (GPS) tracking device on a vehicle and using the device to monitor the vehicle’s movements constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment.

Technological challenges to the Fourth Amendment are not new.

Warren and Brandeis were among the first to recognize the friction inherent in new technology and the right to privacy. In addition to police surveillance of telegraph and telephone data, the authors noted in the 1890 Harvard Law Review, “Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life; and numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops.”

Wiretapping was widely used by law enforcement and even sanctioned by the Supreme Court in 1928 through Olmstead v. United States. In A Social History of Wiretaps, David H. Prices notes the FBI and state governments wiretapped liberally through World War II and the Cold War periods. Then in 1967’s Katz v. US, the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches extended to telephone conversations.

Despite this ruling it is widely believed that wiretapping increased through several presidencies. Then in 1994, Congress passed the Digital Telephone Act, which required all fiber-optic based switches be equipped to facilitate court approved wiretaps. Noted by Price in A Social History of Wiretaps, at the same time the government was wiretapping, the rise of the Internet enabled private companies to begin gathering personal data from computer users.

Passage of the Patriot Act after September 11, 2001 allowed government and financial institutions to examine electronic and computer records of anyone suspected of terrorist activities.

Over the years as more private data was being circulated through various technologies using satellites and the Internet, the public became comfortable with the convenience of using personal devices for communications and computing.

So what are the issues with technology and the Fourth Amendment that courts are grappling with today and how should they be handled?

First, we should understand how the new and relatively inexpensive technologies have changed the game for law enforcement, making long-term and wide-ranging surveillance relatively easy to accomplish even with limited resources.

Justice Samuel Alito, concurring with the judgement of the Supreme Court in United States v. Jones said, “In the pre-computer age, the greatest protections of privacy were neither constitutional nor statutory, but practical. Traditional surveillance for any extended period of time was difficult and costly and therefore rarely undertaken. The surveillance at issue in this case — constant monitoring of the location of a vehicle for four weeks — would have required a large team of agents, multiple vehicles, and perhaps aerial assistance. Only an investigation of unusual importance could have justified such an expenditure of law enforcement resources. Devices like the one used in the present case, however, make long-term monitoring relatively easy and cheap.”

To address the issue of the ease of long-term monitoring with new technology, some legal experts have adopted the “mosaic theory” of the Fourth Amendment. The “mosaic theory” states that long-term monitoring of a suspect can be a Fourth Amendment search even if short-term monitoring is not.

According to Orin S. Kerr, a professor of law at the George Washington University Law School, “This idea which was suggested by the concurring opinions in United States v. Jones, is that surveillance and analysis of a suspect is outside the Fourth Amendment until it reaches some point when it has gone on for too long, has created a full picture of a person’s life (the mosaic), and therefore becomes a search that must be justified under the Fourth Amendment.”

So if newer technologies such as GPS, infrared imagers, digital cameras and audio recorders threaten privacy under the Fourth Amendment, then drones which can carry all these technologies simultaneously, and fly for many hours at very low cost, represent the trifecta of challenges to that privacy.

Law Professor Tom Clancy, who teaches The Fourth Amendment: Comprehensive Search and Seizure for Judges at the National Judicial College, sees the challenge that drone technology brings to the Fourth Amendment.

“Drone technology can be utilized for surveillance so invasively and for 24/7/365 at minimal cost. Plenty of police departments are experimenting with drones and there is currently no case law to protect us.”

Attorney Richard M. Thompson, writing for the Congressional Research Service on Drones in Domestic Surveillance Operations said, “The constitutionality of domestic drone surveillance may depend upon the context in which such surveillance takes place. Whether a targeted individual is at home, in his backyard, in the public square, or near a national border will play a large role in determining whether he is entitled to privacy. Equally important is the sophistication of the technology used by law enforcement and the duration of the surveillance. Both of these factors will likely inform a reviewing court’s reasoning as to whether the government’s surveillance constitutes an unreasonable search in violation of the Fourth Amendment.”

An issue to be examined when discussing the intrusion of technology into one’s privacy is the concept of privacy itself.

Many Americans today have a small modicum of privacy. If they have a smart cell phone with the GPS function enabled to navigate, post to Facebook or LinkedIn or shop at Amazon.com, they leave electronic footprints that law enforcement can legally trace. These Americans, it turns out, understand the intrusions on their privacy as a side effect of using the Internet. That doesn’t mean they like it.

A recent Pew Research Center survey, The Future of Privacy, caught the attention of Judge Herbert B. Dixon and he wrote about it in the Spring 2015 Judges Journal published by the American Bar Association. He reported that 55 percent of Pew’s 2500 respondents said that “privacy as we know it is disappearing. More than half believe their private interests are in jeopardy, that tracking of people’s personal lives for commercial profit will increase and that the government’s access to personal information will increase.”

He said “there is no question that this new notion of privacy will impact Fourth Amendment issues. With new technologies, we can no longer ask what James Madison would say about…”

Paul Ohm, Associate Professor and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at the University of Colorado Law School, writes in The Fourth Amendment In A World Without Privacy, 81 Miss. L. J. 1309 (2012)

“In a world without privacy, a Fourth Amendment focused on privacy becomes nearly a dead letter. Today’s Fourth Amendment has been built around the reasonable expectation of privacy test, but no expectation of privacy will be deemed reasonable in a world without privacy.”

Despite this pessimism about the future of privacy, a Reuters poll conducted in January 2015 on the use of police drones found surprising support. Sixty-eight percent of the 2,405 respondents said they support flying drones to solve crimes and 62 percent support using them to deter crime.

NJC faculty member Hon. V. Lee Sinclair, Jr. said drones versus privacy is a combination of many issues wrapped up into one.

“The first is the flight in air space that raises questions. Then we have the visual capability to hone into micro private areas. Add to this the ability to pick up sound. These are complicated issues with many Constitutional concepts. Start with Katz. Add in Kyllo and Ciraolo. Then throw in US v. Jones on tracking devices and this will be the subject of Fourth Amendment junkies for some time.”

One final observation.

By the time the protections are written on the regulation of drones vis a vis the Fourth Amendment, the next new technology challenging the right to privacy will have already been invented.

This story appeared in the 2015-16 issue of Case in Point, the annual magazine of the National Judicial College.

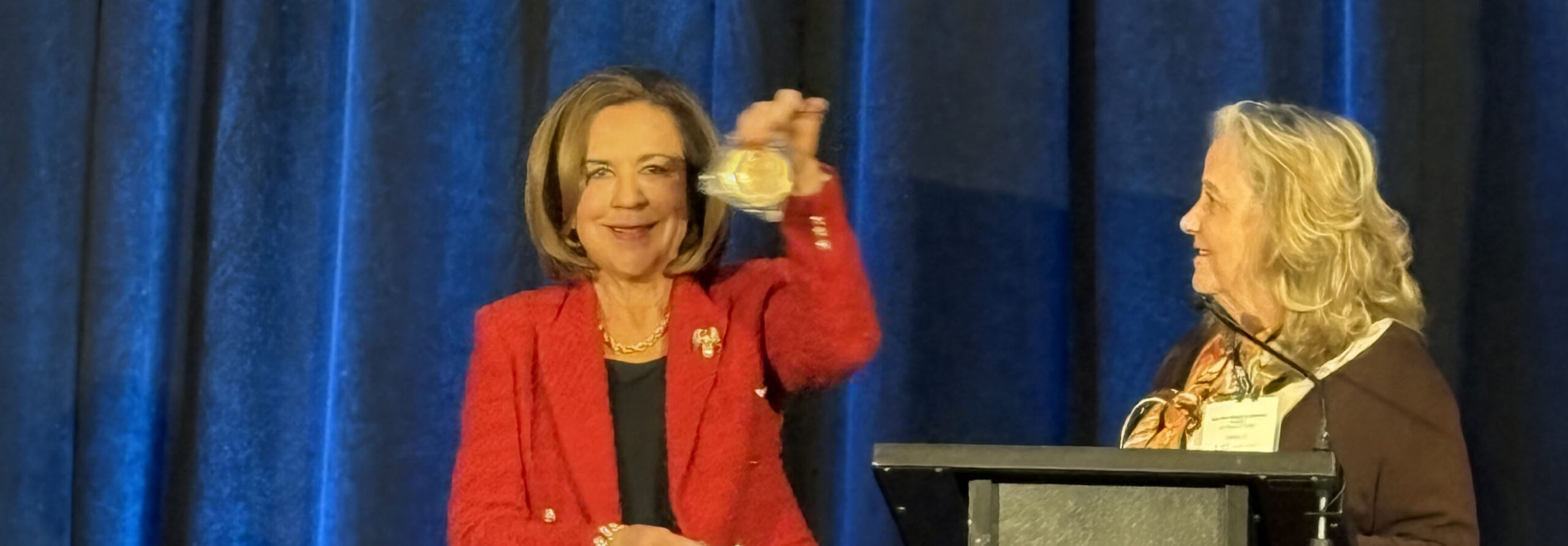

The National Judicial College has awarded Missouri Supreme Court Judge Mary Russell with the Sandra Day O�...

Emeritus Trustee Bill Neukom (left) with former Board of Trustee Chair Edward Blumberg (right) at the NJC 60...

The National Judicial College, the nation’s premier institution for judicial education, announced today t...

The National Judicial College (NJC) is mourning the loss of one of its most prestigious alumni, retired Uni...

As threats to judicial independence intensify across the country, the National Judicial College (NJC) today...