A new book, The Chief Justices, by former Chicago Bar Association President Dan Cotter profiles the 17 men who have held the title Chief Justice of the United States. In this second of two excerpts (Part I can be read here), we learn about Taney’s tenure as chief and his legacy.

The Taney Court

When Taney began his tenure as chief justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, the Court was held in “relatively high prestige” that had been “acquired for the most part during the years when John Marshall was Chief Justice.” The Taney Court issued a series of decisions that substantially narrowed the role of the federal government in economic regulation. Unlike Marshall, he and other Jackson Supreme Court appointees favored the powers of the states over the powers of the federal government.

The Taney Court also issued opinions in a number of noteworthy cases, such as the Charles River Bridge and Amistad cases. The Charles River Bridge case was decided during Taney’s first term as chief justice but had come before the Court six years earlier so still had to be decided. The Taney Court decided cases in a variety of areas, with three major groups dominating his Court: (1) rights of corporations, (2) the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution, and (3) questions of property and slavery.

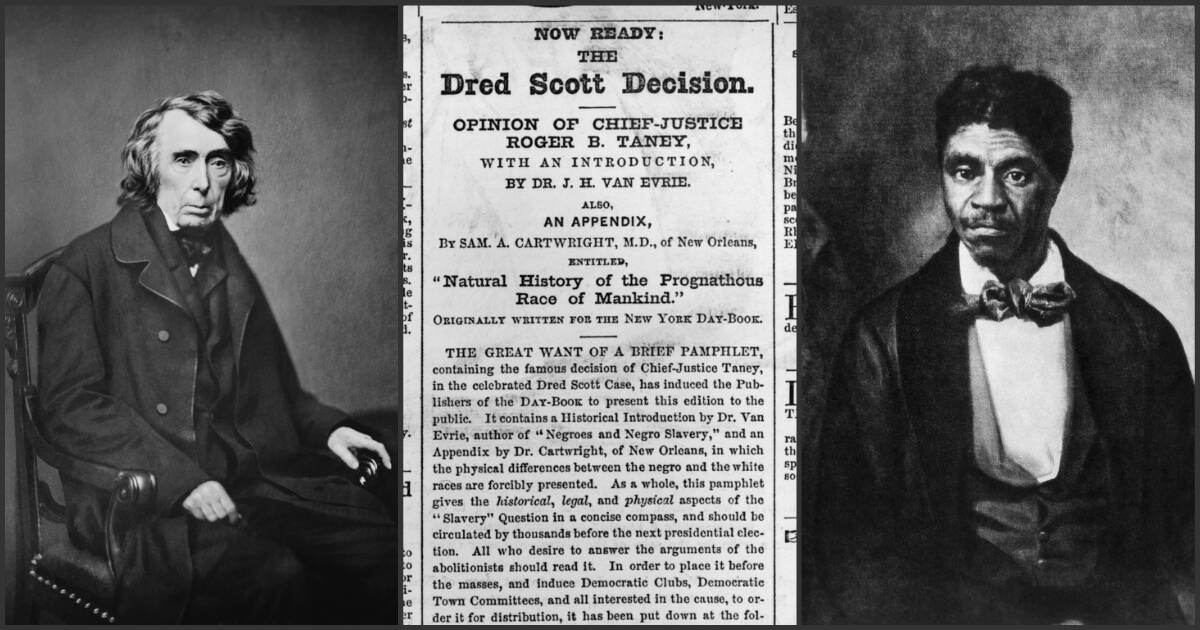

Despite the longevity of Taney as chief justice and the various developments in law the Taney Court made, the Taney Court is remembered most for the 1857 decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, holding by a 7-2 margin that Congress had no authority or power to prevent the spread of slavery into federal territories and that, at the time of the country’s founding, African Americans were not U.S. citizens nor was such citizenship contemplated.

One justice, Benjamin Robbins Curtis, was so upset by the decision that he left the bench, the first and only justice known to have resigned on principle.

Roger Taney’s legacy was made by the Dred Scott decision. When the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill in 1865 to commission funds for a bust of Taney to be placed in the Supreme Court along with his predecessors, Senator Charles Sumner argued against it, calling the Dred Scott decision “more thoroughly abominable than anything of the kind in the history of the courts.”

Taney, the twenty-fourth justice and fifth chief, was the first of thirteen Catholic justices. Currently, five of nine justices are Catholic.

Dred Scott Decision

Dred Scott was born into slavery in Virginia around 1799 but was moved to Missouri where he was sold to Dr. John Emerson, an army surgeon. Given Dr. Emerson’s military career, he moved frequently and took Scott with him. Eventually, Dr. Emerson moved with Scott to the State of Illinois and the Territory of Wisconsin, both free territories. While in the Wisconsin Territory, Scott married Harriett Robinson, another slave who was also sold to Dr. Emerson. In 1838, Dr. Emerson married Eliza Irene Sandford from St. Louis. In 1843, Dr. Emerson died shortly after returning to his family from the Seminole War in Florida. His slaves continued to work for Mrs. Emerson and were, as was common at the time, occasionally hired out to others. In 1846, Dred and Harriet Scott each filed suit in St. Louis to obtain their freedom, on the basis that they had lived in a free state and territory, and the rule in Missouri and some other jurisdictions at the time was “once free, always free.” When the suit reached the Supreme Court of the United States, the main issue presented was whether slaves had standing to sue in federal courts.

Background of the Case

Numerous precedents in Missouri case law, including Rachael v. Walker (1837), established the legal principle of “once free, always free.” The judge declared a mistrial when the case was heard in 1847, and when it was retried in 1850, the St. Louis court ordered Dred Scott free—the Scotts agreed that only Dred’s case would proceed in order to save money and avoid duplicate efforts and all parties agreed that the outcome of Dred’s case would also apply to Harriet. In Scott v. Emerson (1852), the Missouri Supreme Court decided against Scott, reversing the lower court decision, and noting that Missouri law would not be subject to outside antislavery arguments. By its decision, the Missouri Supreme Court overturned the long-held principle of “once free, always free.” The Missouri Supreme Court explained its decision in stark terms and why it was overruling precedents:

Times are not now as they were when the former decisions on this subject were made. Since then not only individuals but States have been possessed with a dark and fell spirit in relation to slavery, whose gratification is sought in the pursuit of measures, whose inevitable consequences must be the overthrow and destruction of our government.

The Controversy

Seeking to have the Supreme Court of the United States opine on the legality of Missouri’s invalidation of the “once free, always free” principle, Scott’s attorneys filed a new suit in federal court, Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sandford (Sanford’s name was misspelled due to a clerical error).

The U.S. District Court for the District of Missouri directed the jury to consider the question of whether Scott was free, or a slave based on Missouri law. Based on the Emerson decision, the jury found that Scott was a slave.

The Supreme Court Decision

Scott appealed to the Supreme Court. Initially, the Supreme Court was inclined to affirm the Missouri Supreme Court decision based on Strader v. Graham (1851), a decision of the Supreme Court allowing the Court to affirm a state supreme court decision without hearing it on the merits. However, some of the justices suggested that the Supreme Court address issues that until then remained unresolved, including those that Sanford’s attorneys raised during the federal lawsuit, such as Scott’s ability to sue in federal court and whether a black person could be a citizen of the United States. The main issue before the Supreme Court was whether Scott had ever been free.

The case originally was argued on February 11–14, 1856, but the justices were divided on their views and with the presidential election of 1856 coming, Taney “was doubtless relieved, when [Associate Justice] Samuel Nelson, declaring himself in doubt on certain points, requested that the case be reargued.” Taney granted Nelson’s request, and the rehearing took place on December 15–18, 1856, after the election was over.

After the oral arguments, and when President-elect Buchanan visited Washington prior to his inauguration, Buchanan wrote Justice John Catron, “asking him whether the Dred Scott case would be decided before the date of inauguration.” Catron inquired and informed Buchanan the case was to be decided at the next conference. Buchanan also wrote to Justice Robert Cooper Grier, attempting to influence his position and have him vote as a Northerner with the majority.

Delivered on March 6, 1857, the Court, by a 7-2 decision, held that blacks were not and could not be citizens of the United States and, as a result, Scott lacked standing to sue in federal courts. The Court also found that Scott had never been free, finding that Congress exceeded its authority when it forbade or abolished slavery in the territories, invalidating the Missouri Compromise. Having found a lack of standing, this second issue should not have been addressed by the Court. Chief Justice Roger Taney wrote for the majority:

In discussing this question, we must not confound the rights of citizenship which a State may confer within its own limits and the rights of citizenship as a member of the Union. It does not by any means follow, because he has all the rights and privileges of a citizen of a State, that he must be a citizen of the United States. He may have all of the rights and privileges of the citizen of a State and yet not be entitled to the rights and privileges of a citizen in any other State. For, previous to the adoption of the Constitution of the United States, every State had the undoubted right to confer on whomsoever it pleased the character of citizen, and to endow him with all its rights. But this character, of course, was confined to the boundaries of the State, and gave him no rights or privileges in other States beyond those secured to him by the laws of nations and the comity of States.

The Dred Scott decision is a landmark decision because it answered questions regarding slavery that the Court had not previously addressed. It is also one of the most infamous decisions, furthering the great divide facing the nation regarding the question of slavery and moving the country further down the path toward the Civil War. The Dred Scott decision undermined the prestige of the Supreme Court and virtually all legal scholars consider it to be the worst decision ever issued by the Supreme Court. The Dred Scott decision was overturned when the Civil War ended, and the Civil War Amendments were ratified. However, the Dred Scott decision began a long period of time where the Supreme Court “declined in popular esteem.” The decision should not have surprised much, given the “Taney Court was staunchly pro-slavery, rejecting states’ rights when Northerners asserted them to oppose slavery.”

Legacy

The Dred Scott decision, rather than eliminating slavery as a national issue of debate, angered Northeners and strengthened the Republican Party, which was anti-slavery. In 1860, Abraham Lincoln won the presidency, and secession ensued by the southern states. Taney remained on the Court, taking the position that the states had a right to secede and also blaming the Republicans and especially Lincoln for starting the war. Taney and Lincoln would butt heads for the remaining time that Taney was on the Supreme Court and, in Ex parte Merryman, Taney held that power to suspend habeas corpus resided in Congress and a president had no power to do so. The Merryman decision was one that Taney filed with a federal circuit court and not as a Supreme Court justice. Toward the end of the Civil War, in 1863, the Supreme Court held in the Prize Cases that President Lincoln had the power to order a blockade and seize ships, with Chief Justice Taney dissenting.

Taney died on October 12, 1864, aged 87.

As noted, the decision issued by the Taney Court in Dred Scott has (fairly) cast a large shadow on the legacy and lasting reputation of Taney. His tenure as chief justice of the Supreme Court “started and ended” with “sharp and lingering controversy.” According to Stevens, the only good to come from the decision was Abraham Lincoln criticizing it and “helped get him elected president of the United States.” But contemporaries were divided on the decision, and despite his dissent in Dred Scott, Curtis referred to Taney as a “man of singular purity of life and character.” More recently, Justice Antonin Scalia, in his dissent in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, referring to Taney’s “great Chief Justiceship,” apparently agreed with Curtis.

Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes once wrote an essay for the ABA Journal entitled “Roger Brooke Taney: A Great Chief Justice.” Jackson wrote:

It is unfortunate that the estimate of Chief Justice Taney’s judicial labors should have been so largely influenced by the opinion which he delivered in the case of Dred Scott. . . . [T]he Dred Scott cased passed into history as an event pregnant with political consequences of the highest importance, and having a most serious effect upon the prestige of the Court. . . . Nothing could be more unjust than to estimate the judicial work of the days of Taney by a disproportionate emphasis upon the decisions which were called forth by the vexed questions growing out of the institution of slavery and the prospect of its extension. Rather I should like to take this opportunity to recognize the importance services of Chief Justice Taney in setting forth principles that are guiding stars in constitutional interpretation. . . .

Notwithstanding those comments and praise, Taney will forever be remembered for the Dred Scott decision. The assessment that “few Chief Justices have dominated the Court as completely as Taney. His tenure served to consolidate and refine Marshall’s Federalist jurisprudence rather than dismantle it in favor of states’ rights” cannot overcome Dred Scott and its aftermath.

Note: This meticulously researched 484-page book includes many hundreds of footnotes. With permission of the author, they have been dispensed with here because of formatting difficulties.

The book is available for purchase through Amazon. Interested readers can buy the book here.

The Hon. Mary-Margaret Anderson (Ret.), a retired administrative law judge with the California Office of Ad...

Happy October, Gaveliers faithful. Are you loving this or what? No one believed a team made up of judges...

Hon. Diane J. Humetewa, the first Native American woman and the first enrolled tribal member to serve as a ...

Retired Massachusetts Chief Justice Margaret H. Marshall has been selected as the 2024 winner of the presti...