By Hon. James Redwine

Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859) was a Frenchman who studied American society during a nine-month tour in 1831 when the United States were still simmering with vitriolic political animus from the 1824 and 1828 elections between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. Adams was elected by the House of Representatives in 1824 and Jackson won via the Electoral College in 1828. After neither election did the United States fall into chaos, even though Jackson won both the popular vote and a plurality, but not a majority, of the Electoral College in 1824.

Four men ran for president in 1824: John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay and William Crawford. Because the Electoral College vote was split in such a way that none of the four received a majority, as required to be elected president under the 12th Amendment to the Constitution, a “contingent” election was held in the House of Representatives. Each state’s delegation was given one vote, and Adams was elected. Jackson and his supporters alleged that Adams and Clay had entered into a “Corrupt Bargain” to shift Clay’s votes to Adams. Regardless, Adams was elected by the House and the country moved on until 1828 when Jackson ran against Adams again.

In his treatise on American democracy, de Tocqueville defined America’s presidential election as “a revolution at law” and described it as follows:

“Every four years, long before the appointed (presidential election) day arrives, the election becomes the greatest, and one might say the only, affair occupying men’s minds…. As the election draws near intrigues grow more active and agitation is more lively and widespread. The citizens divide up into several camps.… The whole nation gets into a feverish state.”

De Tocqueville’s ultimate verdict on America’s democracy was encapsulated in his general verdict on how political controversies were ultimately resolved. His observation was that:

“In America there is hardly a political question which does not sooner or later turn into a judicial one.”

De Tocqueville’s opinion was that the American manner of resolving political issues without bloodshed worked because, unlike European monarchies, the United States citizens respected the law and they did so because they had the right to both create it and change it. Since we get to choose our legislators who write our election laws, and because we can change the laws by changing whom we elect if we are unhappy, we accept the laws as written, including who is ultimately declared the winner of an election.

The laws we have the right to create and change include filing for an elected office, running for that office, who counts the votes, how they are counted, and how and when someone can legally contest an election. That legal procedure applies to all facets of an election cycle. Each state’s legislature has the authority to establish its own procedures in this regard as long as they do not violate federal law.

As an Indiana Circuit Court judge I was involved in a recount of a congressional race, a county clerk general election, a county council general election, a town council election and a county council primary election. The Indiana legislature had enacted and published a clear statutory procedure for each type of election contest, including what role each public official should play in any recount. The statutes demanded total openness and media access to ensure the public could have confidence that if all involved followed the law, a clear winner would be fairly determined. There were time limits, controls and transparency. After a recount result was certified in each contest, life moved on and the eventual losers and their supporters accepted the results because they had had their “day in court”; that is, democratically enacted law was followed, not the arbitrary or partisan activity of individuals.

De Tocqueville compared America’s hotly contested democratic elections to a surging river that strains at its banks with raging waters then calms down and carries on peacefully once the results have been properly certified. From my own experience with several elections and after the recounts of some of them, I agree with de Tocqueville’s analogy.

That is not to say I am for or against any type of recount for any office. I absolutely have no position on whether any candidate for any office should concede or contest anything. My position is simply that as long as the law is properly followed, our democracy can handle either circumstance.

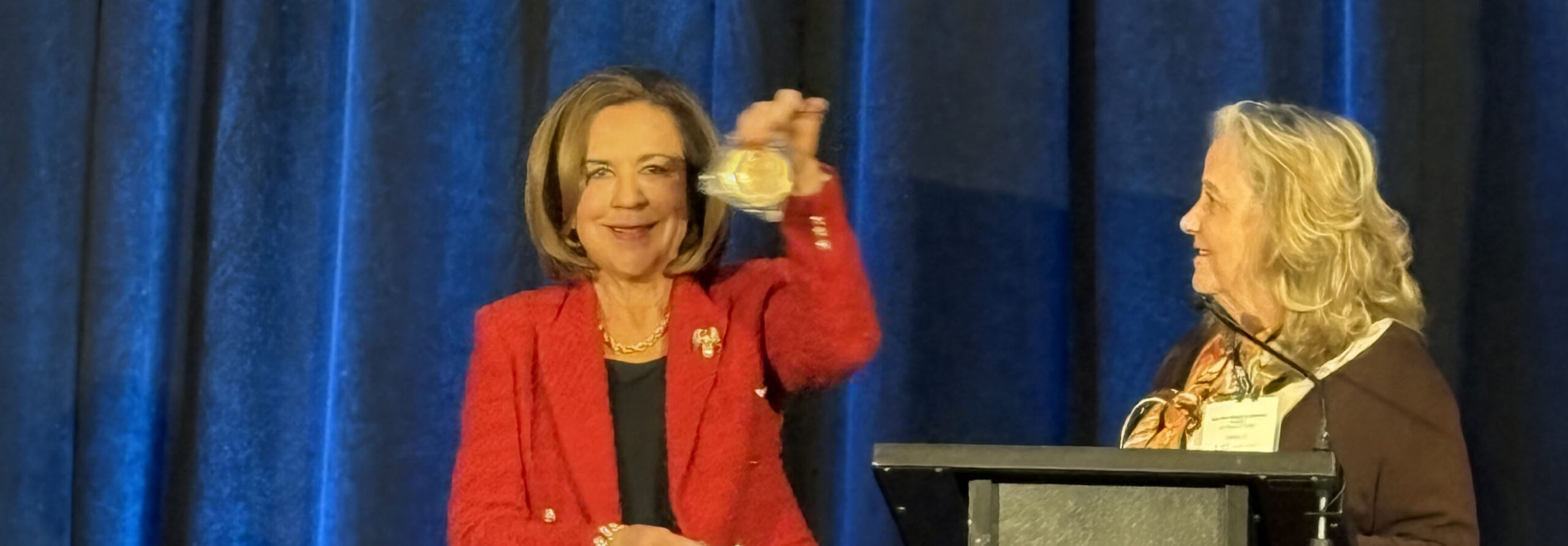

The National Judicial College has awarded Missouri Supreme Court Judge Mary Russell with the Sandra Day O�...

Emeritus Trustee Bill Neukom (left) with former Board of Trustee Chair Edward Blumberg (right) at the NJC 60...

The National Judicial College, the nation’s premier institution for judicial education, announced today t...

The National Judicial College (NJC) is mourning the loss of one of its most prestigious alumni, retired Uni...

As threats to judicial independence intensify across the country, the National Judicial College (NJC) today...