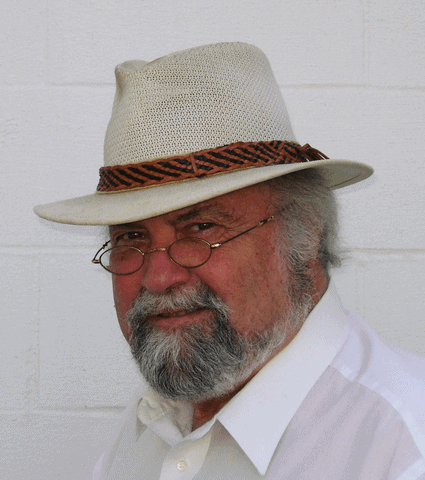

By Hon. Dennis Challeen (Ret.)

I have a friend who was a judge elsewhere and he had a case where a woman was severely, physically abused by her boyfriend. He pleaded not guilty and the judge set a very high bond that he was unable to post. The defendant apparently told the jailers that when he got out he was “going to kill her.” The judge, being aware of this threat, refused to accept any reduced negotiated plea.

After six months in jail the defendant changed his plea to guilty. Believing that after this long delay from when the crime and threat had occurred, he should have calmed down, the judge released him under the order not to go near the woman; he agreed to abide by this condition; and she was notified of his pending release. He proceeded to kill her, and at trial was given life in prison. The judge received a considerable amount of media criticism for allowing this dangerous man out on the streets.

My friend was deeply bothered by this case and I know it went with him the rest of his life. He was tormented by the question of whether he could have done something different that would have saved her life. We other judges who knew him assured him that we would have most likely done the same. It wasn’t a life imprisonment case. The man was only charged with a misdemeanor and sooner or later would have to be released after serving his sentence.

The stark reality is that no judge has the power to protect all potential victims from a deranged person who is willing to forfeit his or her life to exact vengeance upon another. If the state murder statute, which carries life in prison, doesn’t deter, then a piece of paper called a Restraining Order with a judge’s signature on it won’t be any more effective. We all make decisions every day to put caution and distance between us and danger. People move away from obnoxious neighbors and unsafe neighborhoods. There are people who should be avoided at all costs, and unfortunately some of us learn that the hard way.

The right to bail is in our constitution’s Bill of Rights (Amendment VIII), which states: “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.”

Our founders had lived in times where there was no such thing as “bail bonds,” and debtors were cast in prison until they paid, which sometimes was impossible. If family or friends didn’t come to the rescue, a person could die in prison.

Every defendant is presumed to be innocent, and his or her guilt must be proven by the state beyond a reasonable doubt. The rules also presume the defendant should be released upon his own recognizance (promise to return) unless the prosecutor can show to the judge that the defendant is a danger to others or may flee and leave the jurisdiction of the court.

Every judge faces a balancing act between the rights of the accused and protecting the general public and potential victims.

Judges ask for and receive the defendant’s criminal record and a brief study by a court officer to recommend whether the defendant should be released without posting bail. Judges always consider protecting the victim if it is a crime against another person. Consideration also focuses on the defendant’s roots to the community (marriage, grew up locally, relatives in the area, employment record, education, ownership of property, previous convictions — particularly crimes of violence, if released in the past did the defendant make all court appearances).

The question of requiring bond is always controversial because it means people with money or property can make bond, while the poor cannot. Some people are poor by foolish choices; others are poor regardless how hard they work.

The amount of bail required must reflect the ability of the defendant to reasonably raise the cash or premium to a bonding company (who are in the business of making a profit). Bonding companies make sure their risk is minimal and they rarely forfeit money to the court.

When I was on the bench I often advised the accused to find a friend or relative who would pledge to pay the bond amount if the defendant failed to keep court dates. I did this to see whether a family or responsible friend would have faith in the accused; if not, that told me something about the defendant’s reliability. If those who knew him didn’t trust him, I certainly didn’t.

I was often asked how judges arrive at the amounts they set as bond, usually in thousand-dollar increments. My answer may shock you, but the amounts are plucked out of the sky. However, the amounts can be reduced or eliminated later by a motion to reduce and as more facts come into play.

Living in a free society with our constitutional rights is never easy or simple.

Do you have stories to tell from your experiences on the bench or that you’ve heard from other judges? We’re considering collecting them into a book for posterity. Email them to: njc-communciations@judges.org

The Hon. Mary-Margaret Anderson (Ret.), a retired administrative law judge with the California Office of Ad...

Happy October, Gaveliers faithful. Are you loving this or what? No one believed a team made up of judges...

Hon. Diane J. Humetewa, the first Native American woman and the first enrolled tribal member to serve as a ...

Retired Massachusetts Chief Justice Margaret H. Marshall has been selected as the 2024 winner of the presti...