Chief Justice William S. Richardson (HI)

1919-2010

When William Richardson became chief justice of Hawaii, the state was seven years old.

Over the next 16 years, he would establish a legacy as one of the most revered and impactful figures in modern Hawaiian history.

Among other accomplishments, the Richardson court laid the foundation for natural resources law in the islands. Its rulings established the principle that beaches, fresh water, and even new land created from the cooling lava from volcanoes were the shared property of the public, not private property.

Born in Honolulu, Richardson came from a long line of lawyers. His grandfather had been a judge and counsel to Queen Lili’uokalani, the last Hawaiian monarch. But he was raised in a working-class family. According to an obituary in the Honolulu Star Advertiser, in his youth he worked as a newsboy and pineapple hand to make spare change. His father built the family home from surplus and cast-off lumber, and his mother sewed shirts using buttons collected from used clothing.

After earning his law degree at the University of Cincinnati (his parented rented out his room to pay for his legal education), he returned to the islands, which were then still a U.S. territory.

At the time, the islands’ political power was concentrated in the hands of wealthy white residents. Richardson became part of a political revolution of young, mostly Asian (of Japanese descent) Democratic Party politicians who would soon begin dominating elections. He was serving as chair of the state Democratic Party in 1959 when Hawaii gained statehood.

In 1962 he successfully ran for lieutenant governor. Four years later, after Richardson had completed a single term, the Democratic governor nominated him to become chief justice.

Richardson led Hawaii’s supreme court from 1966 until 1982. It was a decidedly progressive court that prioritized the greater good and often looked for precedence in the culture and legal traditions of native Hawaiians.

Hawaii is considered unique among the United States in that its system of laws is built on an ancient and traditional culture. In 1966 Richardson noted that a chief justice in Hawai’i “must live in the past – but not only the past. He must adopt the fundamental principles of the past and bring them into focus with the present. And in Hawaii, the present – like the past – is a time of migration.”

In a seminal water-rights decision, the Richardson court clarified Hawai’i law to establish that it was the state, as successor to the king of old, that owned all water “flowing in natural watercourses.” As it had been the king’s responsibility, the state should now hold the resource in trust for the people, the court reasoned.

Another case established boundaries between public beaches and private property. The Star Advertiser obituary noted, “As a child, Richardson chafed at how difficult it was to get to the beach because so many access points were cut off by private homes. And the memory of having to stand in the water outside the Royal Hawaiian Hotel because the sand was off limits to all but hotel guests stayed fresh in his memory, even in his later years.”

A third case established that any new land created by lava flows from volcanoes became part of the state of Hawai’i, not an extension of any adjacent private property.

Richardson was known for his optimism and for his empathy, especially for working people. He considered it an essential function of the law to protect the powerless from those with great power.

In 1973, Hawai’i established its only law school. Richardson had fought for many years for its creation and remained an active supporter long after its founding. He saw the school as an opportunity for people of modest means to advance socially since cost and distance put law school on the mainland beyond the reach of many islanders. In 1982 when he retired from the supreme court, the law school, at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, was renamed in his honor.

At the law school’s 2005 graduation ceremony, a student honored the school’s 85-year-old namesake with a traditional chant that recalled King Kamehameha’s Law of the Splintered Paddle. The law declared, “Let the old men, the old women and the children go and sleep by the wayside; let them be not molested.”

The unusual title came from a story about the common people of Puna, on the big island, who were fishing one day when the young chief Kamehameha came upon them. Knowing only that a stranger and a chief approached, the men feared trouble and fled; Kamehameha pursued.

When Kamehameha’s ankle caught in a lava crevice, one of the fishermen doubled back and hit him on the head with a paddle, splitting the paddle in two.

Eighty years later, when the fisherman and his companions were brought before King Kamehameha for punishment. Instead of putting them to death, he recognized his own responsibility in causing the incident. He proclaimed the Law of the Splintered Paddle, protecting even the most defenseless from oppression by those with more power and authority.

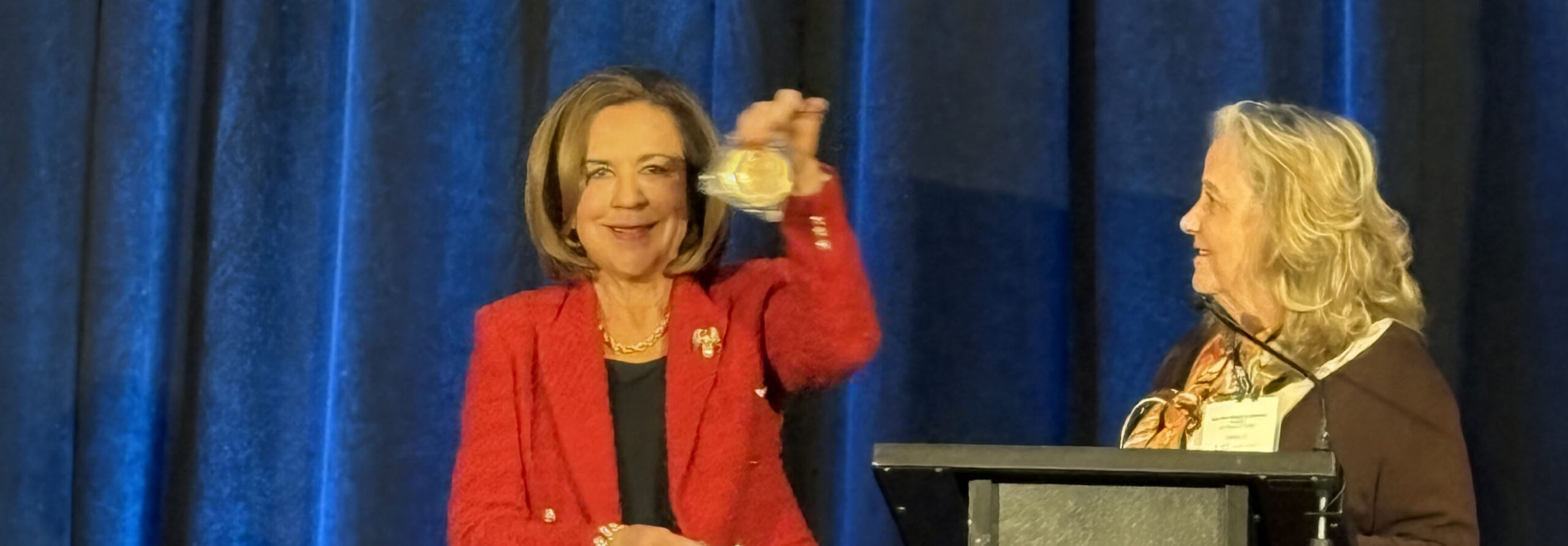

The National Judicial College has awarded Missouri Supreme Court Judge Mary Russell with the Sandra Day O�...

Emeritus Trustee Bill Neukom (left) with former Board of Trustee Chair Edward Blumberg (right) at the NJC 60...

The National Judicial College, the nation’s premier institution for judicial education, announced today t...

The National Judicial College (NJC) is mourning the loss of one of its most prestigious alumni, retired Uni...

As threats to judicial independence intensify across the country, the National Judicial College (NJC) today...