One of Henry Frye’s favorite poems is “It Couldn’t Be Done” by Edgar Albert Guest. The poem includes the lines:

There are thousands to tell you it cannot be done,

There are thousands to prophesy failure

There undoubtedly would have been thousands to tell Henry Frye it couldn’t be done had he announced to his teachers at Ellerbe Colored High School in the 1940s that he was going to become chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court.

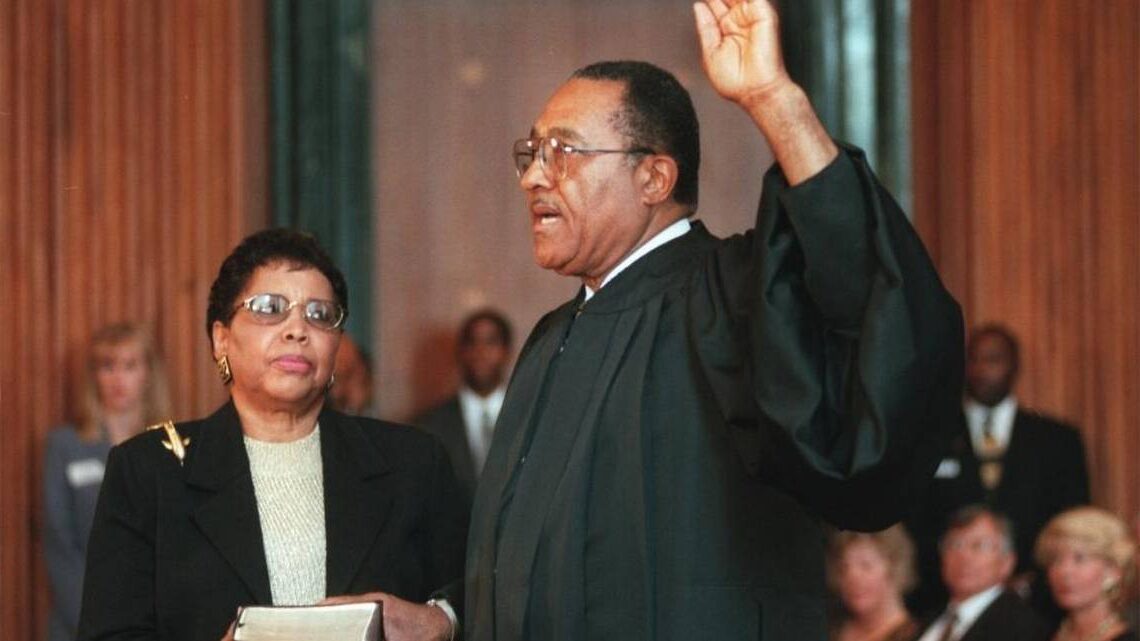

He himself never predicted anything of the sort. But in 1983 he did become the first African-American member of the North Carolina Supreme Court. And 16 years later, this man who in his 20s was denied the right to vote by a phony Jim Crow-era “literacy test” became the court’s first Black chief justice.

In a recent interview, the retired chief, now 88, revealed that after graduating from college he actually had his sights set on dental school. He said a lawyer he respected, J. Kenneth Lee, who would become a prominent Black civil rights champion, told him, “Forget that. You made good grades in school and you care about people. I think you ought to go to law school.”

For a young Black man living in the South at that time, that was easier said than done.

Henrick E. Frye was born during the Great Depression near Ellerbe, a small town in rural Richmond County, North Carolina, south of Greensboro and east of Charlotte. His parents, Walter and Pearl, worked as tobacco and cotton farmers. Henry was the eighth of their 12 children.

He excelled in the study of science at North Carolina A&T State University in Greensboro, a historically black school founded in 1891 as the Agricultural and Mechanical College for the Colored Race. After graduating in 1953, he served two years as a munitions officer in the Air Force in Korea and Japan before returning to North Carolina.

“I didn’t grow up around lawyers, and some people around me didn’t have high opinions of lawyers,” the future chief justice said. During his time in the Air Force, however, he’d met a lawyer who taught English to prisoners in his off-duty hours.

“How much do you get paid?” Frye, the young officer, asked. “He said, ‘I do it for free.’ That impressed me.”

Frye applied to and was accepted into the University of North Carolina School of Law. He was the first African American to be admitted and complete the full three-year curriculum (there had been previous African Americans who transferred in from other schools).

Before starting law school, however, he went to register to vote.

At the election board office in Ellerbe, the man in charge began asking him questions. Frye said the man told him that in order to pass the state’s literacy test, he had to name a certain number of the members of the constitutional convention.

“I said, ‘Why are you asking me these kinds of questions?’ I knew what the law in North Carolina was. All you had to be able to do was read and write a section of the Constitution….”

Frye said the man then pulled a book from behind the counter and said the questions were in the book and since he couldn’t answer them, he did not pass the test and couldn’t register.

It was 1956, and Frye was visiting the office on the same day as his wedding to his wife of now 64 years, Shirley. He said the Black minister who was going to officiate at the wedding came in behind him and got the same treatment.

He reported the incident to a lawyer, who suggested he contact the chair of the Board of Elections. The lawyer added that he thought that if he went back to the office he wouldn’t have a problem.

Whatever may have happened behind the scenes, Frye returned to the election office and found a different person at the counter, a woman, who in short order registered him to vote.

He encountered further institutional racism after law school. After taking and passing the bar, he applied for his law license. First, however, he had to undergo a “moral examination.” Again, the official in charge began asking a lot of strange questions, he said.

“He named an address in Charlotte and said, ‘Have you ever been to that address?’ I said, ‘I don’t know.’ The bottom line was I did not pass my moral examination.”

After reporting the encounter to J. Kenneth Lee, the lawyer who had recommended a legal career to him, and to the head of the state bar, he eventually was granted his license.

Chief Frye went on to a successful legal career, starting in private practice in Greensboro. In 1963 he made headlines when he became the first Black assistant U.S. attorney in the Greensboro office. He was one of the first African Americans to hold such a position in the South.

In 1966 he ran for a seat in the North Carolina House of Representatives and lost. But he tried again two years later and won, becoming the first African American elected to the state house in the 20th century. He served until 1981 and then served two years in the North Carolina Senate.

One of his major accomplishments in the legislature was passing an amendment to the state constitution removing the literacy test and other vestiges of Jim Crow-era measures aimed at suppressing the Black vote. The amendment was ultimately defeated by the voters, but the restrictions it addressed passed out of existence anyway because of the federal Voting Rights Act.

Frye also made a name for himself in the legislature as a poet. He said he would sometimes get bored listening to his fellow law makers make the same arguments over and over. To stay awake, he began rhyming verses to make his point, which he would then read aloud.

“The only bad part about it was that some of the legislators got the thought that I was going to do that every day.”

Late one Sunday night in 1983, North Carolina’s then-governor, Jim Hunt, called Frye at home to ask if he would be interested in an appointment to a seat on the state Supreme Court.

“I talked to my family about it, and they were all supportive except one. My youngest son said, ‘Well, how much does it pay?’ But he finally went along with it.”

Frye was elected to the post in 1984 and re-elected in 1992. Governor James Martin appointed him to the state’s highest judicial post, chief justice, in 1999, replacing the retiring chief justice. He was defeated for election to a full term in 2000 and left the bench the following year.

In “It Couldn’t Be Done,” the lines about the thousands who will prophesy failure are followed by cheery advice to buckle in, grin, take off your coat, and get to work on that task everyone says is impossible.

Just start in to sing as you tackle the thing

That “cannot be done,” and you’ll do it.

“I think it carries a great message,” said the retired chief justice. “Don’t give up, keep trying. That’s my thing.”

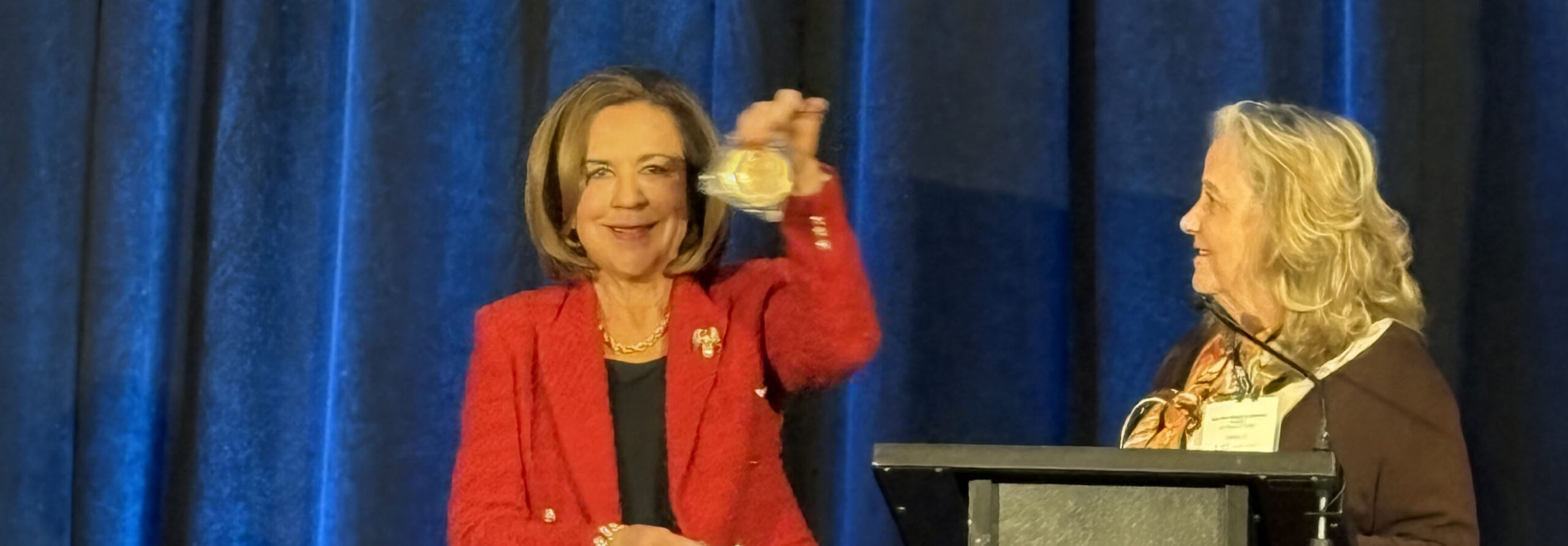

The National Judicial College has awarded Missouri Supreme Court Judge Mary Russell with the Sandra Day O�...

Emeritus Trustee Bill Neukom (left) with former Board of Trustee Chair Edward Blumberg (right) at the NJC 60...

The National Judicial College, the nation’s premier institution for judicial education, announced today t...

The National Judicial College (NJC) is mourning the loss of one of its most prestigious alumni, retired Uni...

As threats to judicial independence intensify across the country, the National Judicial College (NJC) today...