My parents and six siblings were all born in Jamaica, West Indies, but I was born and raised in the Crown Heights and Flatbush sections of Brooklyn, New York. Our neighborhood was culturally diverse. Large numbers of the residents were either immigrants from various countries in the Caribbean or African Americans with southern roots. Most people in my neighborhood looked like me. Their accents were the distinguishing feature.

Being from a large family meant that my village was massive. Celebrations and events included not only my immediate family but aunts, uncles, cousins and “framily” (family friends who were so close we considered them family). It also meant that any missteps were disappointing not only to my parents but to the entire village because they always found out. When I succeeded, everyone succeeded. While they may not have had an extensive formal education, they encouraged me to get good grades, serve my community, and treat people the way I wanted to be treated.

While Brooklyn itself was culturally diverse during this time, the neighborhoods were not. West Indians lived predominantly in Flatbush and Crown Heights; the Jewish community lived together in their neighborhood; the Italian community lived together in their neighborhood; and so on. The result was segregated neighborhoods.

When I was to begin the first grade, my parents were notified that my local school was overcrowded and that I would be bussed to another school. In essence, I became a part of the school system’s attempt at school desegregation. I boarded a bus, traveled each morning out of my neighborhood, passed my “zoned” school, and was schooled in a predominantly White neighborhood.

During those five years of elementary school, I was the only, or one of two, Black students in my class. In middle school, more students were bussed in from my neighborhood and others. During these three years, at least two other Black students were now with me in any given class.

These formative years during the 1970s and early 1980s, especially during middle school, introduced me to racism, bigotry and hate. I was called horrible racist names daily and told to “go home” or “get out of the neighborhood.” Things were thrown at our busses. We were attacked and chased out of the neighborhood on many occasions. As horrible as those experiences were, they taught me to persevere and be resilient and steadfast. They taught me the importance of community. I also learned to run fast!

During these formative years, I learned about injustice, advocacy, taking a stand, and the power of having a village.

At the tender age of 6 or 7, I knew I wanted to become an attorney. Specifically, I wanted to become a criminal defense attorney. My brother had gotten in trouble and ultimately incarcerated. I was committed to defending people like my brother who I believed to have been railroaded, mistreated and wrongfully convicted.

I lived in two completely different worlds and learned that the outcome of any given situation was dependent on which world I was navigating. In school, I was taught that I could trust police officers. In my neighborhood, I was taught to run when I saw the police – not because I was guilty but because I could not trust them. In my neighborhood, I saw people mistreated by the police. I saw friends incarcerated and others killed. In school, my White classmates had more freedom and a different outlook on their life and future. They had different dreams and aspirations.

For high school, I applied to and was accepted into a specialized school in Manhattan, Murry Bergtraum. I learned so much at this school. Not only was the student body diverse, so were the faculty and staff. For the first time, I had teachers who looked like me. Teachers who pushed and encouraged me. Educators who saw my potential and stretched me. Teachers like Mr. Cummings realized that my quick wit and smart mouth could benefit the moot court team and encouraged me to join. (Actually, he promised to go back and change my grade to an “A” if I agreed to join the team. He still owes me an A!)

Mr. Mott introduced me to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library and inspired me to be a voracious reader. He not only required me to read the state-mandated curriculum but introduced me to Black authors such as Alice Walker, Margaret Walker and even Iceberg Slim and Donald Goines.

Mr. Sinclair (no relation) tortured me with “Tess of the D’urbervilles” but also took me to see Broadway plays. Our principal, Ms. Christian, repeatedly told us that “Bergtraum girls were the best in the world!” The list goes on and continued into college, law school and my professional career.

I share my experiences to highlight the fact that our words and actions matter. What we do or say can have a lasting impact on those people with whom we come in contact. As judges, we have the power to change lives. Whether it is mentoring young people and encouraging them to dream big or how we treat a litigant who comes before us. The legal profession is enriched by actively making efforts to include people from different cultures, races and genders, bringing their life experiences and backgrounds to the table.

These differences shape how we think. When we all interact with each other, it expands our perspective. Diversity matters. Equity matters. Inclusion matters. A seat at the table matters. It mattered that I saw positive role models who looked like me. It mattered that when people were spewing hate, others encouraged and empowered me. It matters that people see the benefit of me being at the table.

Thurgood Marshall said, “None of us got where we are solely by pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps. We got here because somebody – a parent, a teacher, an Ivy League crony or a few nuns – bent down and helped us pick up our boots.”

Therefore, I want to publicly thank the teachers, mentors and members of my village who pushed me, encouraged me, caught me, and pulled me alongside them; the ancestors who toiled, fought and sacrificed, for me to have a better life. I especially have to thank those who told me that I would never amount to anything or tried to fill me with negativity and doubt. You, and my faith in God, gave me the drive and confidence to keep striving to reach higher heights. Without all of these factors, I would not be a lawyer, much less a judge, today.

My challenge to you is to step outside of your comfort zone. Get to know someone who does not look like you. Attend an event that you would not usually attend. Read a book that you would not have otherwise read. Be a mentor. Encourage someone. Expand your territory!

Most importantly, as you climb, pull someone else along because chances are, someone did that for you.

In April 2020 Lorrie Sinclair Taylor became the first African-American judge in the history of Loudoun County, Virginia, when the Virginia General Assembly approved her appointment as a General District Court judge. She is a graduate of the inaugural class of the NJC’s Judicial Academy for lawyers who aspire to become judges.

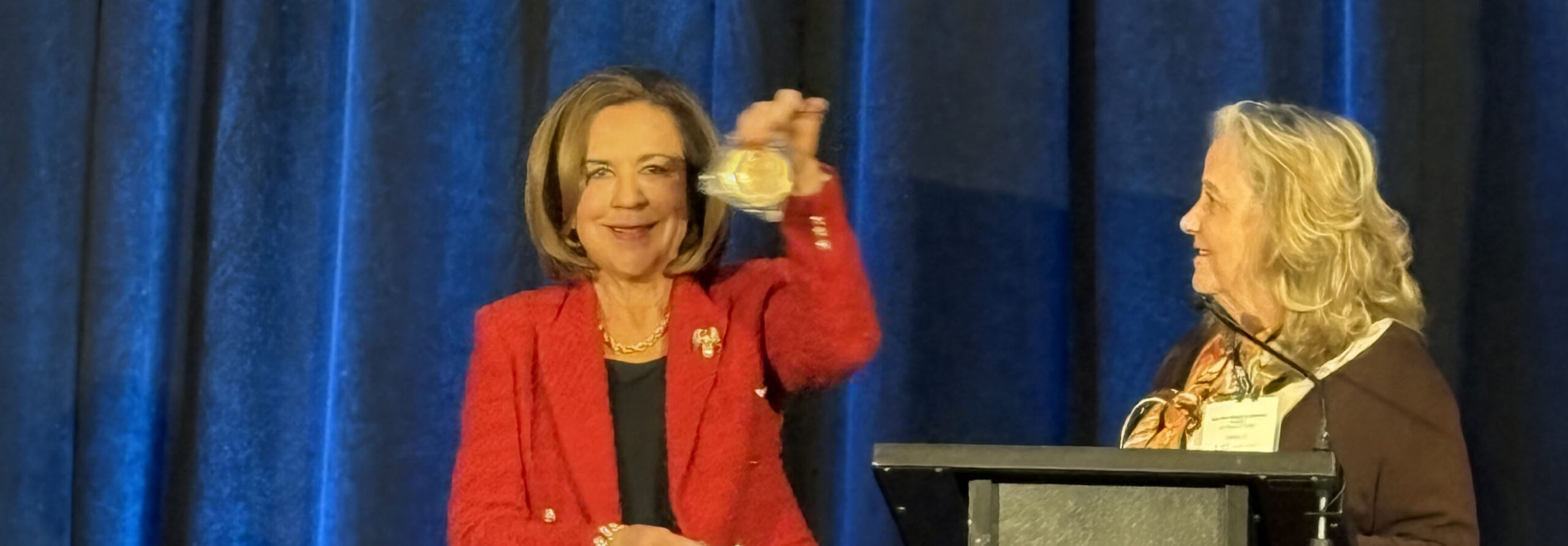

The National Judicial College has awarded Missouri Supreme Court Judge Mary Russell with the Sandra Day O�...

Emeritus Trustee Bill Neukom (left) with former Board of Trustee Chair Edward Blumberg (right) at the NJC 60...

The National Judicial College, the nation’s premier institution for judicial education, announced today t...

The National Judicial College (NJC) is mourning the loss of one of its most prestigious alumni, retired Uni...

As threats to judicial independence intensify across the country, the National Judicial College (NJC) today...