By Hon. Bobbe Bridge (Ret.)

As I write, millions — maybe billions — of words have been dedicated in print and orally to the life and legacy of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg: the law professor; the lawyer for the ACLU winning landmark rulings at the United States Supreme Court; the federal DC Circuit Judge; the Supreme Court Justice; the Notorious RBG. She became an iconic figure in her later years, an idol in a black robe and lace collars — collars that were carefully selected (like her own words) to signal her meaning.

Words highlighted her character and her experience: pioneer (in the battle for gender equality); inspiration (role model); outspoken feminist; mensch; precise (getting it right); fighter (for humanity and for justice). Words lauded her work: in her judicial opinions, whether in dissent or — less frequently — in the majority, Justice Ginsburg embodied a “strategic idealism.” She was bent on revolution, yet she chose not to take to the streets but to head to the law library. “The Constitution,” she opined at her confirmation hearing in 1993, “had been written for a few white men of property, but the story over time was of expanding circles of inclusion — as history, amendments, and jurisprudence expanded American equality to Black people, women, gays, and lesbians.” Linda Hirshman in the Washington Post added, “She wanted to stretch those circles out, to make America fairer, to make justice bigger.”

She chose a steady, deliberate path to achieve her goals. She learned from her mother not to give way to emotions that would sap her strength. Yet her written opinions and her frequent speeches, characterized as they were by sound legal reasoning and respect for precedent, placed a value on reality, lived experience, and consideration of how a particular ruling would impact “real people.” Her vision for our society was simple, as she put it in a 2015 speech: “Men and women, working together, should help make the society a better place than it is now.” Her tactic, “repairing the tears in our society,” is embedded in her Jewish roots, an admonition that we are all obligated to work to repair the world. Her tools were courage, integrity, and speaking truth to power in an effort to bring the power around. She advised us to “fight for the things you care about, but do it in a way that will lead others to join you.”

She’s gone. In spite of her indefatigable spirit — her persistence. In spite of lifting those weights! Why now?? We’re feeling sadness, anger, despair — the 2020 Blues. So many words. What can I add?

It’s personal.

She was a role model for me. Born into a family of modest means, she defied the socially determined odds and her own self-identified obstacles to professional success: being Jewish, a woman, and a mother, like me. Shy and determined, like me. Tiny, like me. She wanted to make the world a better place for all humankind — and she focused on her world — the United States — striving to make it live up to its ideals and preserving its rule of law, equally and equitably applied. Like me.

She too had a bright mother who never went to college and wanted her to be independent — to be fierce but “ladylike.” She too married a man who cared about what was in her head and did everything possible to support her goals and to celebrate her achievements. She too suffered Socratic method abuse in law school (but finished much higher in her Harvard and Columbia classes than I in my UW class). She too was a new mother in law school. But because of her, getting a job in a law firm on graduation was much easier for me. Because of her, it was not a stretch for me to envision myself in a black robe — alas, no lace collar. And because of her (and my mother-in-law), I was emboldened to work through my own self-identified challenges without losing sight of my purpose.

That’s it. That’s what’s personal. She showed the way to a purpose-driven life. She simply wanted girls to have the same opportunities as boys. She wanted the rights of a democratic society, most particularly voting, to be available to all. She grew to understand the intersectionalities of oppression based on race, gender, ethnicity, religion, and differing abilities. She was not a solo act (except in her beloved opera) but rather a part of collective efforts — a link in a chain. She saw herself as standing on the shoulders of the giants who preceded her in the battle for equality and for a more just and equitable world. She knew she wouldn’t be able to finish the task and looked to those in younger generations to carry the work forward. She seemed frail, but she was so strong. Her unparalleled work ethic and discipline allowed her to create an enormous body of work. And yet …

She’s left us with much to do: disabling structural/systemic racial injustice; enacting an Equal Rights Amendment, and much more. So much to be feared: loss of reproductive rights; economic insecurity; health insecurity; voting insecurity; and more. She fought with tenacity, integrity, and purpose. Her fight changed millions of lives for the better. We are without her, and I am/we are grieving. But we are obliged to continue the fight.

It’s personal.

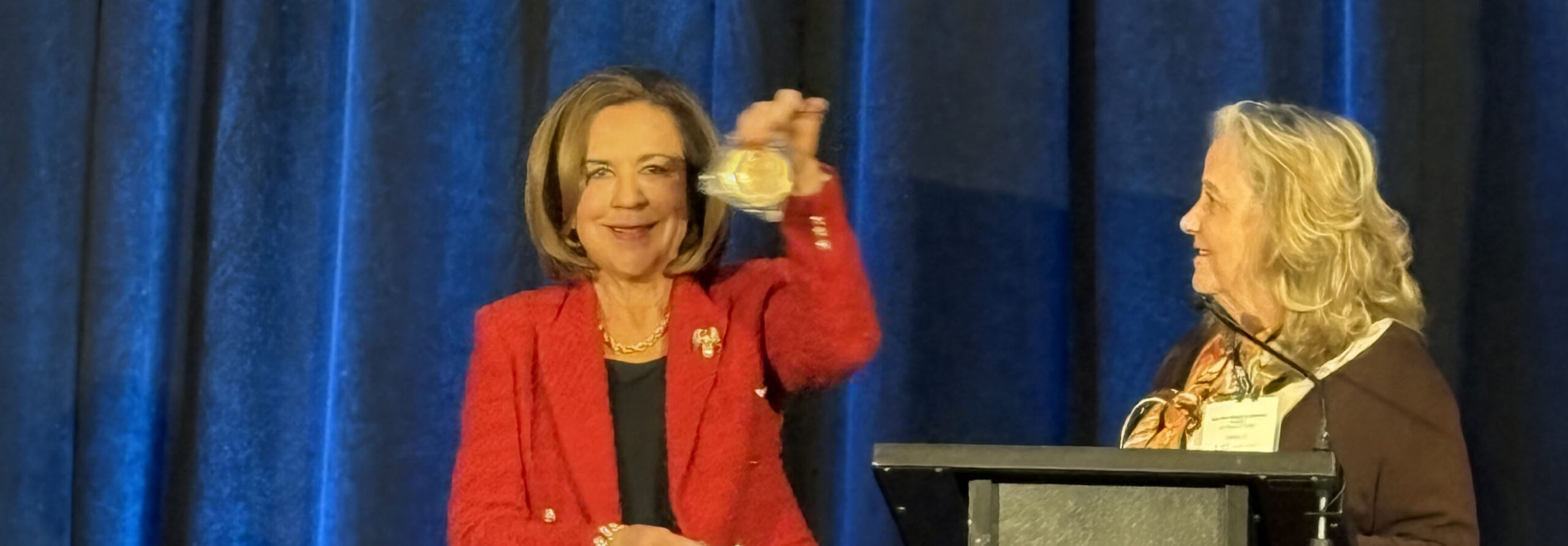

The National Judicial College has awarded Missouri Supreme Court Judge Mary Russell with the Sandra Day O�...

Emeritus Trustee Bill Neukom (left) with former Board of Trustee Chair Edward Blumberg (right) at the NJC 60...

The National Judicial College, the nation’s premier institution for judicial education, announced today t...

The National Judicial College (NJC) is mourning the loss of one of its most prestigious alumni, retired Uni...

As threats to judicial independence intensify across the country, the National Judicial College (NJC) today...