By Judge Neil Edward Axel

District Court of Maryland (retired)

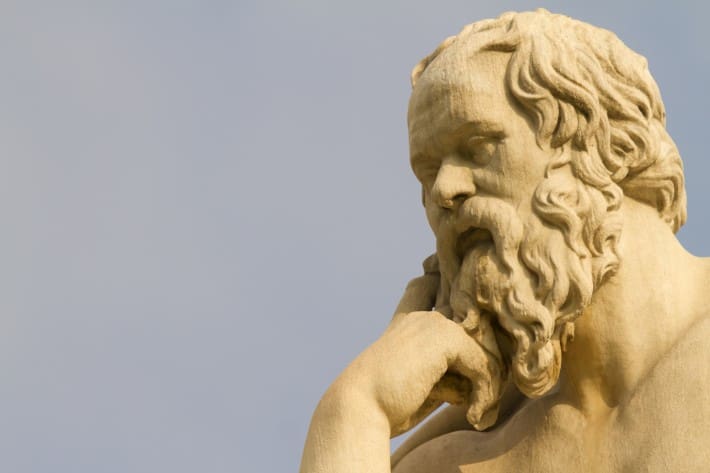

Socrates suggested that there were four aspects of being a fine judge: “to hear courteously; to answer wisely; to consider soberly; and to decide impartially.” In practice, there is no formula or science to achieving these ends. Instead, there is an art to the way in which one presides over their courtroom. This is particularly true as judges are called upon to manage high volume dockets, handle self-represented litigants unlearned in courtroom procedure and protocol, and adjudicate complex emotionally charged family law cases.

When I first came to the bench in 1997, I perceived my new role as a trial judge as requiring me to simply “call balls and strikes”. After gaining some experience on the bench, I came to realize that my role as a judge perhaps involved more than merely calling balls and strikes, and that essentially the nature of judging is how well, how fairly and how reasonably judges exercise discretion. Over time, I came to learn that “exactly what a judge should do cannot be fully described by specific formula”.[1]

Historically, judges sat back and enforced the strict rules of procedure and afforded counsel on each side the leeway to present their cases. The conventional wisdom was that if the process was fair, then through the workings of the advocacy system, litigants with the assistance of their counsel would present the necessary evidence and arguments, following strict rules of procedure that would then result in a just outcome.

The proliferation of self-represented litigants, the focus on domestic violence, new social science and jurisprudential approaches to judging including procedural fairness and problem solving courts have helped shape the 21st Century judge to be more than just an arbiter of facts and law, but now also a great communicator and spokesperson for the judiciary.

Former Chief Judge Robert M. Bell of the Maryland Court of Appeals often noted how one perceives a system is critically important for the health and effectiveness of that system. The opportunity, day in and day out, to impress upon the citizens, whom we serve, what we do, how we do it, and why, is how we earn their trust in a branch of government that has precious little in the way of tangible power. In fact, the only real power a judiciary has is derived from the people it serves; it results from their trust and confidence in that judiciary. If that trust and confidence evaporate, the system is endangered and, indeed, may be mortally wounded.[2]

The Court’s acceptance by the community is based on faith and trust – a faith and trust that we will judge and decide fairly, that we will treat all with respect and dignity, and that we will uphold our respected positions within our community. Confidence in what judges do each day, or in any particular case is less dependent upon whether the “right” decision was reached, but more on the process undertaken to reach that decision.[3] It is in this process, that the art and craft of judging lies.

In recent years, the concept of “procedural fairness” has evolved as an essential ingredient in how favorably the public perceives the judiciary. It is an idea that is concerned with the procedures used by a judge, and not the actual outcome. “People are in fact more willing to accept a negative outcome in their case if they feel that the decision was arrived at through a fair method”.[4] Fairness in this regard includes what we say, how we say it, whether we afford the parties a reasonable yet full opportunity to be heard, and demonstrate respect for all parties, counsel and witnesses involved in the case.

Even the most seasoned trial judge recognizes that over time the nature of judging has changed, and that possibly we can fall into bad habits that over the years are reinforced merely by repetition. Through continuing judicial education, judges can essentially step back and look at not only how they conduct their courtrooms, but also share common experiences with their peers and learn new best practices. There are many techniques one can develop to refine one’s art of judging. One approach is called neutral engagement and permits the judge to make decisions based upon the merits of the case. By conducting the proceedings in an even-handed manner and providing explanations for what the judge is doing, the judge can “ensure that the evidence gets before them and that the process is neutral”. Used appropriately, neutral engagement promotes the elements of procedural fairness by affording the parties voice, neutrality, respect and trust.[5]

Particularly with self represented litigants, judges may need to obtain critical information in order to make an informed decision. This requires judges to at times seek out or gather the necessary information by asking neutral questions of the parties or witnesses. Judges can ask neutral questions or identical questions to each side to ascertain the facts at least as perceived by each party. In asking questions, however, the court must maintain its neutrality, and must avoid questions that suggest skepticism on the part of the judge. Examples of neutral questions might include:

“Give me a little more information about . . .”

“Help me understand . . . “

“Give me some specific details about . . . “[6]

Once the facts and positions are fully presented to the judge, the court must weigh that evidence then decide the matter. In making a decision the court should make clear to the parties that it has considered the evidence, considered the arguments and make its decision in accordance with applicable law. The decision should explain the issues considered, the evidence presented and how applicable law applied to the facts as found by the court. The decision should try to avoid legal jargon and be expressed in a way so that all parties will at least understand how and why the decision was reached. They may not agree with it, but the goal is for each party to leave the courtroom feeling as though they had their day in court, and that their positions were at least considered by the court.

Other techniques that judges can add to their repertoire in order to refine their art and craft of judging include:

- Welcoming the parties by name at the commencement of each case e.g. “good morning Mr. Jones (Plaintiff); good morning Ms. Johnson (Defendant)”.

- When necessary, attempt to use or ascertain the correct pronunciation of each party’s name.

- At the beginning of the hearing, explain the purpose of the proceeding and how the hearing will be conducted.

- Create the best time to adjudicate more complicated matters. If you are handling a high volume docket and an otherwise routine matter appears as though it will take some considerable amount of time for the parties to present their issues, consider resetting the matter to another time when you can allocate additional time.

Further, “judging is a context-driven activity, and one that draws to a great degree on processes not fully articulable”.[7] The 21st Century trial judge must be a patient listener, a good communicator and a fair arbiter. Eye contact, use of plain English, and proactive listening have all become important skill sets for judges, in addition to the more traditional skill sets. In the case of self-represented litigants, can the Court do fundamental justice, if because of a litigant’s lack of knowledge of evidence or procedure, we don’t have the facts upon which to make a decision.

Each judge in their individual courtroom projects the face of judiciary, with the ability to demonstrate how well our government works and how well the judiciary functions in an ordered society. Being a judge means “accepting the responsibility to represent the justice system at your very best – to exhibit patience, tolerance, and understanding”.[8] There is no science to how to do this, only the art that trial judges develop throughout their tenure from experience and from collaborative learning with one’s peers.

Footnotes

[1]Cynthia Gray, Reaching Out or Overreaching: Judicial Ethics and Self Represented Litigants (AJS 2005).

[2] William D. Missouri, An Interview with Chief Judge Robert M. Bell, The Judges’ Journal (American Bar Association, Winter 2011).

[3] In all litigation, there are two or more parties. Reaching the right decision typically will satisfy one of the parties, but if the hearing appeared biased, or a party perceived that he or she was mistreated, or failed to have the opportunity to be heard, then parties will not leave the courtroom with confidence in the work of the judiciary.

[4] K. Burke & S. Leven, Procedural Fairness: A Key Ingredient in Public Satisfaction, 44 Court Review 4, 6 (2007-2008).

[5] D. J. Wilson & M.B. Hutchins, Practical Advice from the Trenches: Best Techniques for Handling Self-Represented Litigants, 51 Court Review 54 (2015)(citation omitted).

[6] Module D, Curriculum on Ensuring the Right to Be Heard for Self-Represented Litigants, NCSC Center on Court Access to Justice for found at http://www.ncsc.org/~/media/Microsites/Files/access/Module%20D%20Guide%20Draft%208-8-13.ashx

[7] Chad M. Oldfather, Of Judges, Law and the River: Tacit Knowledge and the Judicial Role, 2015 Journal of Dispute Resolution 155, 156 (2015).

[8] Joseph P. Nadeau, What It Means to Be a Judge, The Judges’ Journal 34, 35 (American Bar Association Judicial Division, Summer 2000).

Judge Axel is an instructor for the NJC and will be teaching during 21st Century Traffic Issues in Omaha, NE on October 27th.

Related Courses

- Advanced Bench Skills: Procedural Fairness, February 2-3, 2017 (Miami, FL)

- Mindfulness for Judges, November 6-9, 2017 (Sedona, AZ)

The Hon. Mary-Margaret Anderson (Ret.), a retired administrative law judge with the California Office of Ad...

Happy October, Gaveliers faithful. Are you loving this or what? No one believed a team made up of judges...

Hon. Diane J. Humetewa, the first Native American woman and the first enrolled tribal member to serve as a ...

Retired Massachusetts Chief Justice Margaret H. Marshall has been selected as the 2024 winner of the presti...