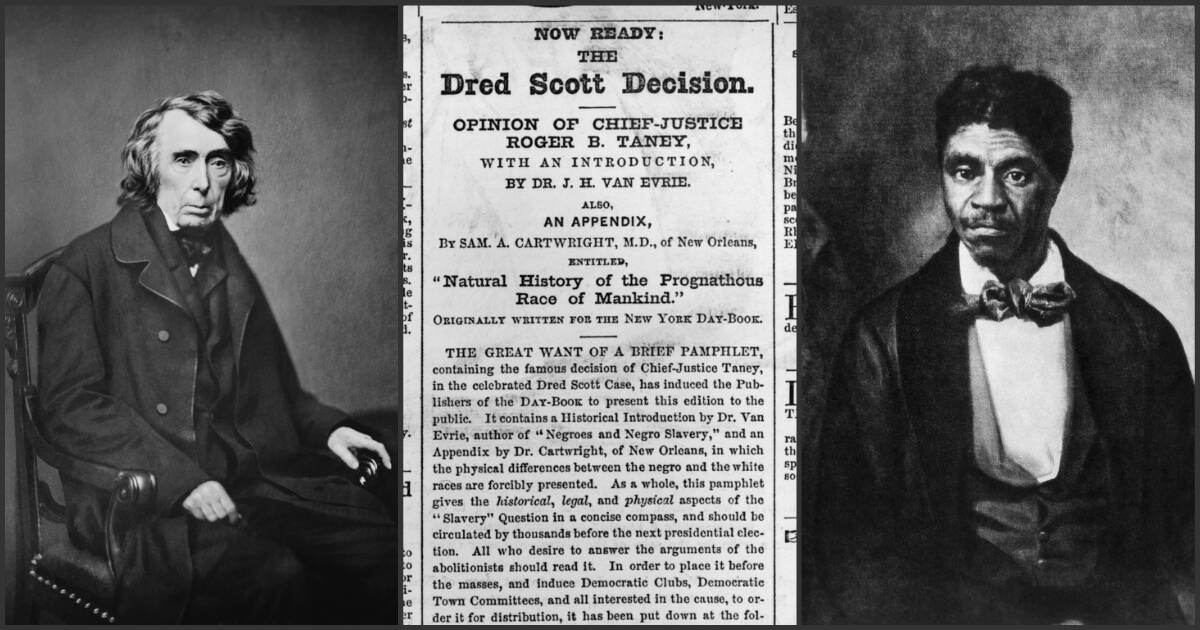

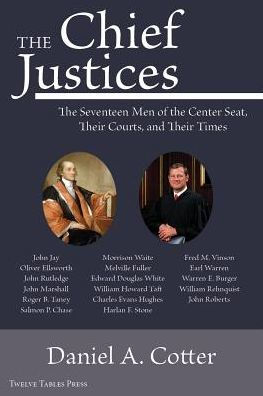

Chief Justice John Marshall, the nation’s fourth, served thirty-four and a half years in that role. Roger B. Taney, who succeeded Marshall, served for twenty-eight and a half years. The two are the first and second longest serving chief justices. Taney’s tenure would be marked by continued national struggles over the institution of slavery, and his Court’s decision in Dred Scott has not only been assailed as wrongly decided but also an event that helped contribute to the South’s secession from the Union and Civil War. During his last years on the court, he was a nemesis of President Abraham Lincoln. Contemporaries and future judges and legal scholars consider Taney to be a decent judge, but his legacy is tarnished and reduced significantly because of Dred Scott.

Roger Brooke Taney was born in Calvert County in southern Maryland on March 17, 1777. He was raised Catholic by his parents, Michael and Monica. Michael was a tobacco plantation owner who was the fifth Michael in the Taney line, a family that had come to Calvert County around 1660. Michael also served as a first lieutenant in the Maryland state militia. At the time of Taney’s birth Catholics in America represented a distinct religious minority. Until Taney was 15 years old, his education consisted of private schools and tutors, and then he entered Dickinson College, obtaining his bachelor’s degree in 1795 as his class valedictorian.

Taney chose a career in law, reading law at the law office of Jeremiah Townley Chase, a chief justice of the General Court of Maryland. At the time Taney read law at Chase’s office, the General Court “was an institution of great importance.” In 1799, Taney was admitted to the bar and set up shop in Annapolis, “trying to find enough work to justify his remaining there, but with little success.”

Taney was elected to the Maryland House of Representatives the same year he became a member of the bar and served one term before returning to private practice after losing reelection. The seat he held in the state house was one his dad held just before him. Around the time of his loss for reelection, his predecessor as chief justice, John Marshall, was beginning his long tenure as chief justice and “was building the Supreme Court into one of the most powerful institutions in the country.”

Taney originally was a Federalist, but because of the War of 1812 controversy in Maryland, the Federalists splintered and Taney became aligned with the “Coodies” and became the “King Coody.” He supported Federalist positions “such as a national bank” but “also believed in states’ rights, particularly on the issue of slavery.” Taney had emancipated slaves he inherited from his father, but his states’ rights views were clear on slavery—Taney “believed the federal government had no right to limit the institution of slavery and that questions involving slavery should be resolved by individual states.”

He married Anne Key—a sister of “The Star-Spangled Banner” author and lawyer Francis Scott Key—in 1806, and the couple had seven children. Of the seven children, the only boy died when he was three years old and would have been the only child of the Taneys to be raised Catholic like his father.

Considered one of the promising young lawyers in Maryland, Taney fluctuated between governmental service and private practice over the course of his career.

Despite originally being a Federalist, Taney strongly supported Andrew Jackson and left the Federalists to become a Democrat. From 1816 to 1821, Taney served in the Maryland Senate.

After a very successful law practice, Taney was elected Maryland attorney general in 1827. In 1831, he resigned from his state position to become acting secretary of war for a short period before taking another Cabinet post as attorney general of the United States. The appointment was well received by the local Virginia and Maryland press, with one paper excitedly stating:

“A lawyer surpassed by none in the country, a gentleman whose name is identified where it has been heard, with everything that is pure and elevated in character, a ripe scholar. . . .”

Views on Slavery

Despite providing manumission to his slaves and also defending slaves in a case during his career, Taney was an anti-abolitionist, and as attorney general, he expressed his views in two opinions that were consistent with subsequent decisions he wrote as chief justice of the Supreme Court, including the Dred Scott decision. In a case involving a South Carolina law that required that free negroes on foreign ships coming into port be seized, Taney asserted slave states had the right to protect themselves against laws that would result in the importation of free negroes, stating in his opinion:

The African race in the United States even when free, are everywhere a degraded class, and exercise no political influence. The privileges they are allowed to enjoy are accorded to them as a matter of kindness and benevolence rather than of right. . . . They were not looked upon as citizens by the contracting parties who formed the Constitution. They were evidently not supposed to be included by the term citizens. And were not intended to be embraced in any provisions of the Constitution but those which point to them in terms not to be mistaken.

“In this fashion Taney stated his doctrine as to the social and legal position of negroes in the United States, the doctrine which was to be hotly condemned twenty-five years later when announced in his opinion in the Dred Scott case.” His argument in the South Carolina matter was that “a legislature was the sole judge as to the proper exercise of the powers which belonged to it.”

Failed Nomination to Treasury Secretary

In 1833, President Andrew Jackson nominated Taney for Treasury Secretary, but the Senate eventually rejected his nomination, at least in part due to the divisive nature of his views on slavery. In addition, Taney had “been employed at the Union Bank as an attorney” and also had views that were at odds with the banking industry, who worked diligently to make sure Taney’s nomination was rejected. President Jackson had delayed formally submitting Taney to the Senate for confirmation for nine months, during which time Taney held the position and was instrumental in the demise of the National Bank of the United States, demanding all funds be withdrawn from the bank and “sealing the bank’s fate.” Following his defeat for Secretary of the Treasury, Taney returned to private practice in Maryland. Things were tough for Taney as he had given up his private practice when he was working as Secretary of the Treasury and his work with trying to close the Bank of the United States made him no friends.

Supreme Court Nomination

A defiant President Jackson next nominated Taney in January 1835 for the position of associate justice to replace the retiring Associate Justice Gabriel Duvall. On January 15, 1835, Jackson submitted Taney’s nomination to the Senate. Taney was respected and “had friends among the respectable conservatives of the country, including Chief Justice Marshall,” who sent Senator Benjamin Watkins Leigh a note informing the senator Marshall had positive information regarding Taney. The Senate rejected the nomination by “postponing its decision indefinitely after a close vote” of 24 to 21.

When John Marshall died after a stagecoach accident in early July 1835, President Jackson did not disclose whom he would nominate to fill the vacancy of chief justice, but many believed that it would be Taney. On December 28, 1835, Jackson submitted Taney’s name for chief justice. Taney was confirmed after a long and heated opposition by a close Senate vote, 29-15, on March 15, 1836. Many senators were not present, as other matters occupied the Senators, and “the National Intelligencer lamented the fact that the lateness of the hour had prevented fuller attendance.” Taney was very partisan and President Jackson rewarded his “partisan warrior who helped [him] kill the Bank of the United States.”

The fact that after the 1834 elections, Jacksonian Democrats controlled the Senate represents a key distinction between this final nomination and Taney’s previous failed nominations for public office and likely led to his long awaited successful confirmation. Taney was officially sworn in on March 28, 1836, and presided until his death on October 12, 1864. Taney’s initial work as chief justice had him on circuit in the Fourth Circuit, hearing cases there. On January 9, 1837, “Taney sat with his brethren of the Supreme Court for the first time.”

Jackson thought very highly of Taney and looked often to him for advice and guidance, all the way through the end of his Presidency. Jackson asked for Taney’s help in drafting Jackson’s farewell speech, which Taney did. The speech revealed much of Taney’s thinking, which was released on March 4, 1837. Among other things, the farewell speech “urged that citizens of every state studiously avoid everything calculated to wound the sensibility or offend the just pride of the people of other states.”

Note: This meticulously researched 484-page book includes many hundreds of footnotes. With permission of the author, they have been dispensed with here because of formatting difficulties.

The book is available for purchase through Amazon. Interested readers can buy the book here.

Hon. Diane J. Humetewa, the first Native American woman and the first enrolled tribal member to serve as a ...

Retired Massachusetts Chief Justice Margaret H. Marshall has been selected as the 2024 winner of the presti...

Dear Gaveliers Fans: I am delighted to announce the appointment of our first Gaveliers coaches, profiled...

Fans, I could not be more proud of the work our players put in over the summer. The difference between h...

As the 2024 Election moves in to its final weeks, just over half of trial judges who responded to a survey ...